Human beings are the only creatures who can make themselves miserable. Other animals certainly suffer when they experience negative events, but only humans can induce negative emotions through self-views, judgments, expectations, regrets and comparisons with others. Because self-thought plays such a central role in human happiness and wellbeing, psychologists have devoted a good deal of attention to understanding how people think about themselves.

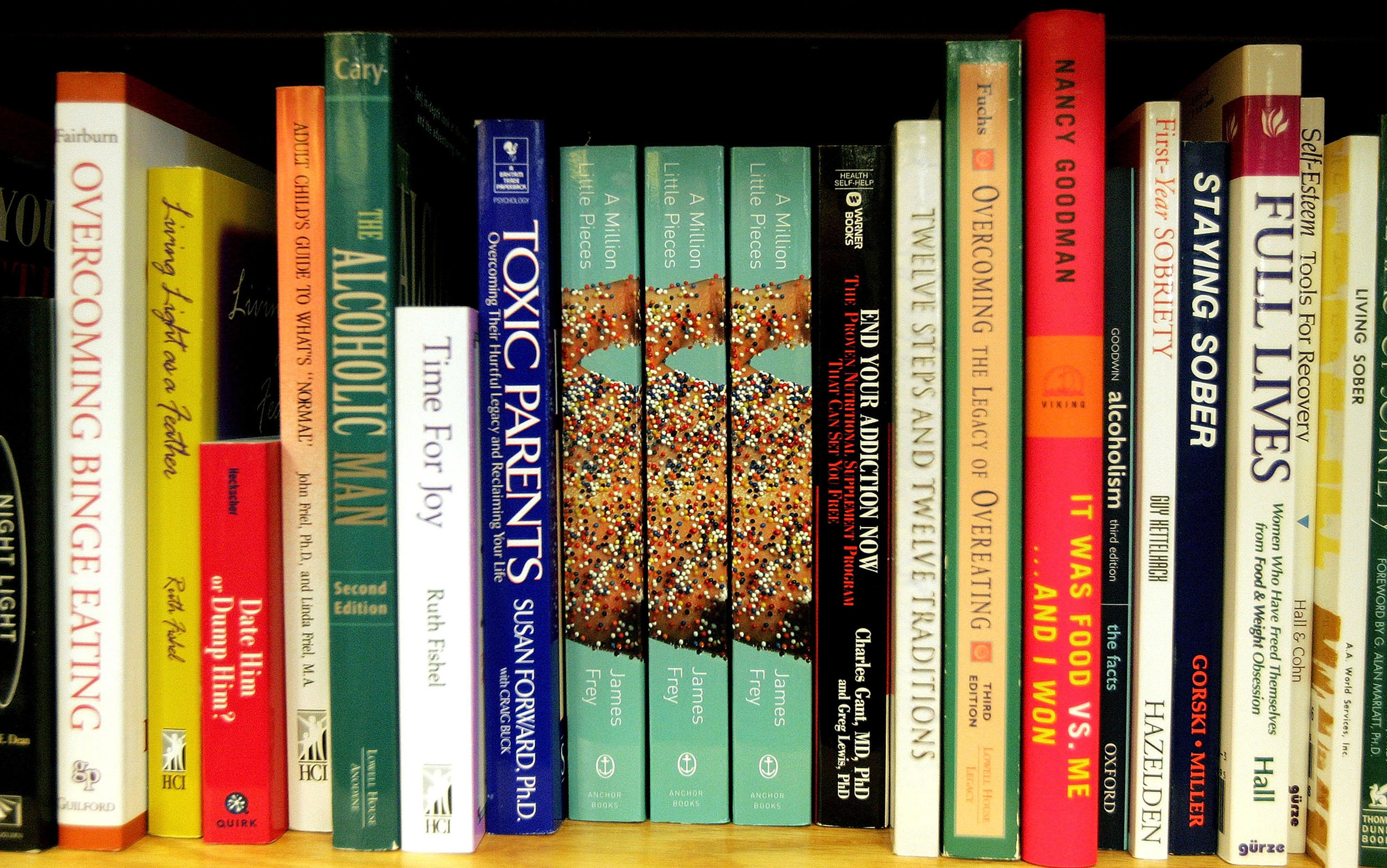

For many years, the experts have focused on self-esteem. Research has consistently shown that self-esteem is related to psychological wellbeing, suggesting that a positive self-image is an important ingredient in the recipe for a happy and successful life. Seeing this link between self-esteem and an array of desirable life outcomes, many parents bent over backwards to ensure that their children had positive views of themselves, teachers tried to provide feedback in ways that protected students’ self-esteem, and many people became convinced that self-esteem should be widely promoted as a remedy for personal problems and social ills. The high-water mark of the self-esteem movement occurred in the 1980s when the California State Assembly authorised funds to raise the self-esteem of its citizens, with the lofty goal of solving problems such as child abuse, crime, addiction, unwanted pregnancy and welfare dependence. Some legislators even hoped that, as a side benefit, boosting self-esteem would enhance the state’s economy.

On one level, this emphasis on self-esteem seemed well-founded. Psychological research shows that success and wellbeing are associated with high self-esteem, and that people with lower self-esteem suffer a disproportionate share of emotional and behavioural problems. Yet, self-esteem has not lived up to its billing. Not only are the relationships between self-esteem and positive outcomes weaker than many suppose, but a closer look at the evidence shows that self-esteem appears to be the result of success and wellbeing rather than their cause. Although thousands of studies demonstrate that high self-esteem is associated with many good things, virtually no evidence shows that self-esteem actually causes success, happiness or other desired outcomes.

Despite the failure of the self-esteem movement, no one would doubt that certain ways of thinking about oneself are more beneficial than others. We all know people who create a great deal of unhappiness for themselves simply by how they think about and react to the events in their lives. Many people push themselves to meet their own unreasonable expectations, berate themselves for their flubs and failures, and blow their difficulties out of proportion. In an odd sort of way, these people are rather mean to themselves, treating themselves far more harshly than they treat other people. However, we all also know people who take a kinder and gentler approach to themselves. They might not always be happy with themselves, but they accept the fact that everyone has shortcomings and problems, and don’t criticise and condemn themselves unnecessarily for the normal problems of everyday life.

These two reactions to shortcomings, failures and problems might appear to reflect a difference in self-esteem but, in fact, the key difference involves not self-esteem but rather self-compassion. That is, the difference lies not so much in how people evaluate themselves (their self-esteem) but rather in how they treat themselves (their self-compassion). And, as it turns out, the latter appears to be far more important for wellbeing than the former. Of course, people prefer to evaluate themselves favourably rather than unfavourably, but self-compassion has the power to influence people’s emotions and behaviours in ways that self-esteem does not.

To understand what it means to be self-compassionate, think about what it means to treat another person compassionately, and then turn that same orientation toward oneself. Just as compassion involves a desire to minimise the suffering of others, self-compassion reflects a desire to minimise one’s own suffering and, just as importantly, to avoid creating unnecessary unhappiness and distress for oneself. Self-compassionate people treat themselves in much the same caring, kind and supportive ways that compassionate people treat their friends and family when they are struggling. When they confront life’s problems, self-compassionate people respond with warmth and concern rather than judgment and self-criticism. Whether their problems are the result of their own incompetence, stupidity or lack of self-control, or occur through no fault of their own, self-compassionate people recognise that difficulties are a normal part of life. As a result, they approach their problems with equanimity, neither downplaying the seriousness of their challenges nor being overwhelmed by negative thoughts and feelings.

Kristin Neff, a developmental psychologist at the University of Texas at Austin, first brought the construct of self-compassion to the attention of psychological scientists and practitioners in 2003. Since then, research has shown that self-compassion is robustly associated with every indicator of psychological wellbeing that has been investigated. People who are higher in self-compassion show greater emotional stability, are more resilient, have a more optimistic perspective, and report greater life satisfaction. They are also less likely to display signs of psychological problems such as depression and chronic anxiety.

People who are high in self-compassion deal more successfully with negative events – such as failure, rejection and loss – than people who are low in self-compassion. Whether the problem is a minor daily hassle, a major traumatic event or a chronic problem, people who treat themselves with compassion respond more adaptively than people who don’t. Just as receiving compassion from another person helps us to cope with the slings and arrows of life, being compassionate to ourselves has much the same effect.

In one study, we asked people to answer questions about the worst thing that had happened to them in the past four days. Although self-compassion was not related to how ‘bad’ participants rated the events they reported, people who were high in self-compassion had less negative, pessimistic and self-critical thoughts about the events, and experienced fewer negative emotions. Self-compassionate people also indicated that they tried to be kind to themselves in the face of whatever difficulties they experienced, much as they would respond to a friend with similar problems.

Self-compassion was particularly helpful for older people who were in poor physical health

Self-compassion might be particularly useful when people confront serious, life-changing experiences. For example, a recent study showed that those who had recently separated from their long-term romantic partners showed less distress about the breakup if they were high in self-compassion.

Getting older brings undesired changes, many of which involve lapses or failures, as when people can’t remember things or have trouble performing everyday tasks. Even though they would treat their friends’ struggles with kindness and compassion, many older people become intolerant and angry, criticising themselves and bemoaning their inability to function as they once did. Others, meanwhile, seem to take ageing more in their stride, accepting their lapses, and treating themselves especially nicely when they have particularly bad days.

Our research shows that people who are higher in self-compassion cope better with the challenges of ageing than those who are less self-compassionate: they had higher wellbeing, fewer emotional problems, greater satisfaction with life, and felt that they were ageing more successfully. Self-compassion was particularly helpful for older people who were in poor physical health. In fact, as long as they were high in self-compassion, people with health problems reported wellbeing and life satisfaction that was as high as those without such problems.

Likewise, we found that self-compassion was related to lower stress, anxiety and shame among people who were living with HIV. Because they were less self-critical and ashamed, those who were higher in self-compassion were also more likely to disclose their HIV status to others. Something about being self-compassionate led individuals confronting a serious, life-changing illness to adapt more successfully.

To understand how self-compassion works, consider how people respond to negative events. When we are upset about something, our reactions stem from three distinct sources. First is the instigating problem and our analysis of the threat that it poses to our wellbeing – what psychologists call the primary appraisal. Whether we are dealing with a failure, rejection, a health problem, losing a job, a speeding ticket or simply a misplaced set of car keys, a portion of our emotional distress is a reaction to the negative implications of the event.

Second, people analyse their ability to cope with the consequences of the problem. Those who think that they cannot handle the problem emotionally will be more upset than those who think that they’ll make it through.

Third comes blame and guilt. When problems arise, we often think about the role that we played – the extent to which we were responsible and what, if anything, this says about us. People often experience additional distress when they believe that the problem arose through their own incompetence, stupidity or lack of self-control. Of course, assessing one’s responsibility is sometimes useful, but people often go beyond an objective assessment of their responsibility to blaming, criticising and even punishing themselves. This self-inflicted cruelty increases whatever distress the original problem is already causing.

Treating oneself compassionately helps to ameliorate all three of these sources of distress. One can reduce some of the initial angst by soothing oneself, just as one might soothe another person’s upset through concern and kindness.

In The Compassionate Mind (2009), Paul Gilbert, a British psychologist who has explored the therapeutic benefits of self-compassion, suggests that self-directed compassion triggers the same physiological systems as receiving care from other people. Treating ourselves in a kind and caring way has many of the same effects as being supported by others.

When people do not add to their distress through self-recrimination, they can look life more squarely in the eye and see it for how it really is

Just as importantly, self-compassion eliminates the additional distress that people often heap on themselves through criticism and self-blame. Again, the parallel with other-directed compassion is informative. I might not be able to make my friend who lost his job feel better, but I certainly won’t make him feel worse by telling him what a failure he is. Yet, people who are low in self-compassion talk to themselves in precisely such discourteous ways.

One central feature of self-compassion that helps to lower distress is what Neff calls common humanity. People high in self-compassion recognise that everyone has problems and suffers. Millions of other people have experienced similar events, and many are dealing with similar problems right now. Although recognising one’s connections with the shared human experience might not reduce our reactions to the original problem, it does remind us not to personalise what has happened or to conclude that our problems are somehow worse than everyone else’s. Viewing one’s problems through the lens of common humanity also lowers the sense of isolation people sometimes experience when they are suffering. It helps to remember that we’re all in this together.

Importantly, self-compassion is not just positive thinking. In fact, self-compassion is associated with a more realistic appraisal of one’s situation and one’s responsibility for it. When people do not add to their distress through self-recrimination and catastrophising, they can look life more squarely in the eye and see it for how it really is. Self-compassionate people have a more accurate, balanced and non-defensive reaction to the events they experience.

Most research on self-compassion has examined its relationship to emotion, but it also has implications for people’s motivation and behaviour. Strong emotions can undermine effective behaviour by leading people to focus on reducing their distress rather than managing the original problem. If unchecked because a person lacks self-compassion, negative reactions foster denial, avoidance and a difficulty or unwillingness to face the problem, leading to dysfunctional coping behaviours. To the extent that self-compassionate people respond with greater equanimity, they respond more effectively to the challenges they confront.

For example, in one study, university students who fared worse than desired on an exam subsequently performed better on the next test if they were high rather than low in self-compassion. Presumably, students low in self-compassion beat themselves up and overreacted, which led them to avoid the issue. Students high in self-compassion surveyed the situation and their role in it, and took steps to improve in the future. Similarly, in our study of people living with HIV, participants who were low in self-compassion indicated that shame about being HIV-positive interfered with their willingness to seek medical and psychological care, whereas those high in self-compassion took better care of themselves. Self-compassion was related both to better psychological adjustment and more adaptive behaviours.

Some people resist the idea that they should be more self-compassionate. Many people assume that self-compassion reflects Pollyanna-ish thinking, denying reality or, worse, self-indulgence. In this view, self-compassion means ignoring one’s problems, shirking responsibility, having low standards, and going easy on oneself. People who believe that being tough on oneself motivates hard work, appropriate behaviour and success worry that self-compassion will undermine their performance.

These concerns reflect a lack of understanding of what self-compassion actually involves. It is not indifference to what happens or how one behaves. Nor is it a blindly positive outlook or an excuse to be lazy or shirk responsibility. Instead, self-compassion is based on wanting the best for oneself. Just as compassion for other people arises from a concern for their wellbeing and a desire to relieve their suffering, self-compassion involves desiring the best for oneself and responding in ways that promote one’s wellbeing. Self-compassionate people want to reduce their current problems, but they also want to respond in ways that promote their wellbeing down the road, and being lazy and unmotivated is not likely to help. Self-compassionate people realise when they have behaved badly, made poor decisions or failed, and they are sometimes unhappy with themselves or with events that occur. But, paradoxically, taking an accepting and compassionate approach to oneself at such times can help to maintain motivation and improve performance.

In one study, inviting people to think about a negative behaviour in a self-compassionate manner led participants to accept more personal responsibility for that behaviour. Viewing one’s problems with a gentle, caring perspective allows people to confront their difficulties head-on without minimising them. They know that a certain amount of self-judgment is needed to maintain desired behaviour, but they are no more critical toward themselves than needed. People who seek what’s best for themselves recognise that they don’t need to punish themselves to know that good behaviour and hard work are important.

Self-compassion is a teachable skill: people can learn to become more self-compassionate. Studies have demonstrated that even brief exercises instructing people to think about a problem in a self-compassionate manner can have positive effects. Other studies show that when psychologists help their clients to master the techniques, their level of anguish abates.

The first step in cultivating self-compassion is to start noticing instances in which you are not being nice to yourself. Are you telling yourself harsh and unkind things in your mind? Do you punish yourself by pushing yourself too hard or depriving yourself of pleasure when things go wrong? Would you treat a loved one this way under similar circumstances?

A self-compassionate person recognises the problem, fixes it if possible, and moves on without making a dramatic production out of it

If you catch yourself treating yourself badly and increasing your distress, ask yourself why. Is it because you think that being hard on yourself helps to motivate you, makes you behave appropriately, or increases your success? To some extent, you might be correct: negative thoughts and feelings do help us to manage our behaviour. The question, though, is how badly you need to feel in order to motivate yourself. People who are low in self-compassion often make themselves feel far worse than needed to stay on track. A little bit of self-criticism can go a long way.

When bad things happen or you behave in a less-than-desirable way, remind yourself that everyone fails, misbehaves, is rejected, experiences loss, is humiliated, and experiences myriad negative events. That doesn’t mean that these events are OK, but it does mean that there’s nothing unusual or personal in what happened. A self-compassionate person recognises the problem, fixes it if possible, deals with it emotionally, and moves on without making a dramatic production out of it.

Finally, learn to cultivate self-kindness. Treat yourself nicely, both in your own mind and in how you behave toward yourself. Many people are surprised to see that they are often much nicer to other people than to themselves.

Fortunately, people can respond self-compassionately no matter how they feel about themselves at the time. Unlike self-esteem, which is based on favourable judgments of one’s personal characteristics, self-compassion does not depend on viewing oneself positively or liking oneself. In fact, self-compassion is often most beneficial when events undermine one’s sense of competence, desirability, control or value. It is much easier to treat oneself nicely than to evaluate oneself positively.

Self-compassion is hardly a panacea for the struggles of life, but it can be an antidote to the cruelty we sometimes inflict on ourselves. Most of us want to be nice people, so why not be as nice to ourselves as we are to others?